The Bourbon Restoration was an attempt by both the French monarchy and the victorious coalition powers to close the Pandora’s box of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic era. Though many wanted a complete restoration of the ways of the Ancien Régime, this was practicable. France and the victors — namely, Britain, Prussia, Russia, and Austria — instead settled on a restored Bourbon monarchy but with a charter, which made the French government a constitutional monarchy. However, the franchise was absolutely tiny.

Here, we’re going to provide a timeline of the Bourbon Restoration. This was a roughly 16-year period, from 1814-1830, when the Bourbon dynasty was restored and ruled France after Napoleon. This period of history is of immense importance, both to the history of France and to Europe overall.

Table of Contents

Timeline of the Bourbon Restoration

After Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russian and retreat in 1812-1813, followed by the victorious of the newly assembled coalition armies in 1813-1814, Bonaparte finally had to admit defeat. On April 2, 1814, the French Senate proclaimed Napoleon’s forfeiture of the imperial throne, followed on April 6 by Napoleon’s official signed abdication. This is where our timeline of the history of the Bourbon Restoration begins, in April 1814.

The First Bourbon Restoration: April 6, 1814-May 3, 1814

On April 6, 1814, the French government invited Louis XVIII to occupy the restored throne. On May 3, Louis XVIII returned to Paris.

Charter of 1814: June 4, 1814

In 1814, under pressure from the victorious Coalition powers, Louis XVIII, who believed himself to be the rightful king of France since 1795, granted the Charter of 1814. This document, introduced after rejecting a constitution proposed by the Provisional Government and Senate, sought to strike a balance by maintaining elements from both the Revolution and the Empire, while also re-establishing the Bourbon dynasty. Framed as a compromise, the Charter established a limited monarchy where the king held significant authority and was deemed “inviolable and sacred,” aligning more with a limited monarchy than a parliamentary one.

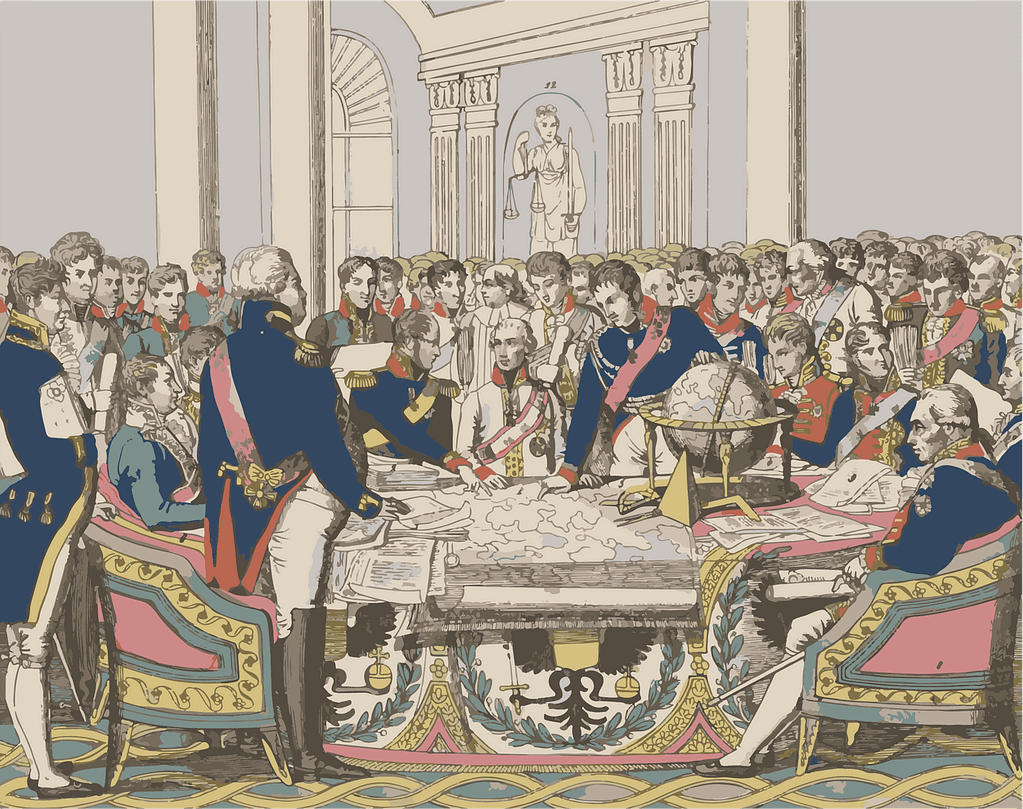

Congress of Vienna Starts: June 24, 1814

The meeting of the victorious coalition powers as well as the defeated French, convoked to draw up a settlement for post-Napoleonic Europe. The Congress of Vienna and its outcome would influence European international relations for years to come, under the guise of the so-called Concert of Europe.

Napoleon Escapes from Elba: February 26-March 1, 1815

Having been kept informed of the political climate in France after the First Bourbon Restoration, Napoleon managed to escape on a couple of ships and at Golfe-Juan, between Cannes and Antibes, on March 1, 1815.

Napoleon Declared an Outlaw: March 13, 1815

Proclaimed by the victorious powers at the Congress of Vienna, by declaring Napoleon an outlaw, they reject any possibility of him or his offspring ruling France.

Congress of Vienna Ends: June 9, 1815

With the signing of the Treaty of Vienna, overseen by the Austrian statesman Metternich, a final settlement was reached on the post-Napoleonic international order. Borders were redrawn and the old balance of power was restored to Europe.

The Hundred Days: March 20-July 7, 1815

Napoleon entered Paris on March 20, followed by a regular army of 140,000 and volunteer forces of approximately 200,000. This initiates the so-called “Hundred Days.” On March 23, with the army having rallied to Napoleon, Louis XVIII, sought refuge abroad and published an order in Lille dismissing the army. On June 16, 1815, Napoleon’s scored victory at the Battle of Ligny, against the Prussian troops of General Blücher. But then, on June 18, Napoleon and his army were finally defeated at the Battle of Waterloo by Anglo-Prussian troops of generals Wellington and Blücher. On June 22, Napoleon abdicated for the second time.

The Second Bourbon Restoration: July 8-August 11, 1815

With Napoleon’s final defeat and abdication, Louis XVIII returned to Paris on July 8. On July 16, by royal decree, Louis XVIII disbanded the existing French army in order to organize a new one. Later, on July 24, he issued an order condemning 57 people for having served Napoleon during the Hundred Days after having sworn allegiance to Louis XVIII. As part of the army reform, on August 11, another order of Louis XVIII was issued, concerning the organization of the departmental legions and the organization of the new army.

Chambre Introuvable: August 14-22,1815

The so-called Chambre introuvable (“unfindable chamber”) wins the legislative elections, producing a chamber dominated by royalists, specifically “ultra-royalists.” The chamber was given this name by the king because he couldn’t dream of finding one so favorable to his throne. Soon, however, this chamber will be challenged.

Duke of Richelieu’s Ministry: September 26, 1815

A former émigré of moderate taste, the Duke of Richelieu becomes head of government and forms the first Richelieu ministry. This came after the dismissal of the Ministry of Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord by King Louis XVIII of France. Richelieu’s ministry would last over three years, being dissolved on December 29, 1818, and replaced by the Ministry of Jean-Joseph Dessolles. Following Talleyrand’s resignation, Louis XVIII appointed the Duke of Richelieu to assemble a cabinet primarily comprising Ultras and counter-revolutionaries opposed to Bonapartism and republicanism. This cabinet initially implemented the “Second White Terror”, leading to the exile, imprisonment, or execution of numerous revolutionaries. However, post the 1816 elections, a Doctrinaire-majority Parliament prompted a cabinet reshuffle, replacing several ministers with moderates. This reformed cabinet enacted significant laws, such as the “Saint-Cyr Law” abolishing nobility privilege in the military, and the “Lainé Law” expanding suffrage and introducing direct voting. By 1817, a new Liberal leftist faction emerged in the Chamber of Deputies, intensifying the rivalry between Richelieu and the popular Doctrinaire Minister Élie Decazes. Richelieu eventually resigned in December 1818, having lost the support of both the Ultras and the Doctrinaires.

Law Against Regicides: January 12, 1816

The legislation enacted on January 12, 1816, often referred to as the anti-regicide law or the “amnesty law”, was introduced by Louis XVIII and approved by the first legislative body of the Second Restoration. This law extended amnesty to those who had backed Napoleon Bonaparte during the Hundred Days, with the exception of his family members and those deputies who had advocated for the execution of Louis XVI in 1793 and subsequently supported Napoleon. These individuals were sentenced to exile, with 171 members of the convention being prohibited from remaining within the country’s borders. This law, sought after by the extremist royalists, represented a period of Legal Terror.

End of the Chambre Introuvable: September 5, 1816

Taking advice from Decazes, Louis XVIII feels forced to dissolve the Chambre introuvable, which had been dominated by the ultra-royalists. The latter became a problem when they had come into conflict with the ministry of the Duke of Richelieu, a trusted man of Tsar Alexander I who at this time was at the apogee of international standing due to Russia’s enormous effort and military forces for defeating Napoleon.

1816 French Legislative Election: September 25-October 4, 1816

Legislative elections were held in France on September 25 and October 4, 1816, in order to elect the first legislature of the Second Restoration. The franchise is severely limited to only citizens paying a certain amount of taxes being eligible to vote. All electors elected three-fifths of all deputies in the first round. In the second round, the most heavily taxed voted again to elect the remaining two-fifths of deputies. The result was:

| Moderate Royalists | 136 | 52.7% |

| Ultra-royalists | 92 | 35.7% |

| Republicans and Bonapartists | 20 | 7.8% |

| Liberals | 10 | 3.9% |

| Total | 258 |

École Polytechnique Reopening: January 17, 1817

The École Polytechnique was a creation of the French Revolution, originating in 1794. It was then militarized under Napoleon after 1804. This university had been shut down by the Bourbon Restoration. But on January 17, 1817, Louis XVIII reopens it under the name of the Royal Polytechnic School. To many Frenchmen, it seems that the king is keeping with a generally moderate political scheme.

Concordat of 11 June 1817

On June 11, 1817, a concordat was agreed upon between France and the Holy See but was never ratified, leaving the 1801 Concordat in place until the 1905 law separating Church and State. Cardinal Ercole Consalvi, representing Pope Pius VII, and the Comte de Blacas, representing King Louis XVIII, led the negotiations. Although the Concordat of 1817 echoed the introduction of the Concordat of Bologna, it introduced new restrictions on its “re-establishment.”

1817 French Legislative Election: September 20, 1817

Legislative elections were held in France on September 20, 1817, during the Second Restoration, to choose delegates to the Chamber of Deputies. It was the first of three elections (the others coming in 1818 and 1819) under a new law that called for legislative elections to be held annually in one-fifth of the nation’s departments. The election was a clear defeat for the ultra-royalists, who lost all their seats. Until then confined to a few individuals, the liberals, led by the banker Jacques Laffitte, constituted a second opposition group at the left of the Government.

Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle: September 29-November 21, 1818

The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle was a diplomatic meeting involving France and the victorious allied powers of Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia, which had defeated France in 1814. Its primary goals were to discuss the withdrawal of the occupation forces from France and renegotiate the reparations owed by France. The congress resulted in a friendly agreement where France restructured its reparations debt, and the allied forces withdrew from France within weeks. The occupation formally ended on September 30, 1818, with full evacuation completed by November 30. The Congress also restored France’s position as a European power, and financially, France initially owed 700 million francs but offered to pay 265 million, partially in the form of French bonds. The main achievement of the Congress was the definitive end of the wars from 1792 to 1815, the closure of all claims against France, and the recognition of France as an equal and full member of the Concert of Five Powers, although disagreements among the powers began to emerge in subsequent years over various international issues. Crucially, as a result of this congress, France was allowed to enter into the new Quintuple Alliance, alongside Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Britain; France, with the Bourbon dynasty restored, now stood for maintaining the status quo.

Serre Laws: March 22-June 9, 1819

The Serre laws received their name in honor of Hercule de Serre, minister of justice for Louis XVIII, who presents them to the Chamber. These three draft laws establish a liberal regime for the press:

- The elimination of prior restraint

- Newspapers can be published as long as the name of the owner of the newspaper is shown

- For the press to be held liable for something criminal, the published article must have provoked a crime; it cannot be criminalized arbitrarily anymore.

- Journalists will not be judged by a magistrate but by a jury of civilians drawn by lot

These laws are adopted on May 17, May 26, and June 9, 1819.

Ministry of Élie Decazes: November 19, 1819

On November 19, the Ministry of Élie Decazes was formed after the dismissal of the Ministry of Jean-Joseph Dessolles by Louis XVIII. This ministry would last into the new year, when it was dissolved on February 17, 1820, and replaced on February 20 by the second ministry of Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis de Richelieu.

Assassination of the Duke of Berry: February 13, 1820

Assassination of the Duke of Berry, youngest son of the Count of Artois, nephew of Louis XVIII and third heir of the dynasty, by a Bonapartist to extinguish the elder branch of the Bourbons. The Duchess of Berry turns out to be pregnant with the “miracle child”.

Death of Napoleon: May 5, 1821

The former emperor days in exile on St. Helena.

Coronation of Charles X of France: May 29, 1825

Charles X, brother of Louis XVIII and Louis XVI, is crowned king of France, and revives the tradition of coronations in Reims.

Le Figaro Newspaper Founded: January 15, 1826

A very famous and still-running French newspaper, Le Figaro, was established by the singer Maurice Alhoy and the writer and politician Étienne Arago.

Domestic Unrest: May 18-October 29, 1826

From March 17 to May 3, 1826, jubilee demonstrations took place in Paris, in honor of the monarchy and the death of Louis XVI. Shortly after the jubilee demonstrations in Paris, in response to similar demonstrations in Rouen on May 16, civil disturbances erupted from May 18 to May 24, 1826. This disturbance had an anti-clerical tinge, with rioters targeting preaching missionaries. In the fall, beginning on October 12, similar unrest aimed at missionaries broke out in Brest. Lastly, starting on October 29, 1826, another similar anti-clerical disturbance engulfed Lyon.

Fan Affair: April 30, 1827

Also called the Fly-Whisk Affair, was a diplomatic incident in which the Dey of Algiers — Hussein ibn Hussein — slapped the French consul Pierre Deval with a fly-whisk, after a contentious back-and-forth over debts owed by merchants contracted by France decades earlier to Algiers. This incident would spark a massive retaliation by the French, leading to the French conquest of Algeria.

Treaty of London and Greek Independence: July 6-October 20, 1827

On July 6, 1827, the United Kingdom, Russia, and France met and hammered out the Treaty of London. It aimed to mediate between the Greeks and Ottomans, proposing that Greece become an Ottoman dependency with conditions set if the Sultan rejected mediation. Despite relying on its perceived naval strength, the Ottoman Empire’s refusal led to its defeat by the Allied powers at the Battle of Navarino, which ultimately paved the way for Greek independence. The treaty also restricted Russia from seeking territorial gains or exclusive commercial benefits from Turkey. However, the subsequent Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 and the Treaty of Adrianople, which granted significant territories to Russia and recognized Greek independence, were seen by European powers as a breach of Russia’s commitments from the 1827 treaty. In the end, the Ottomans rejected this, and on October 20, 1827, the coalition powers destroyed the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Navarino. These further intensified issues related to the Eastern Question.

End of the Villèle Ministry: January 5, 1828

Joseph de Villèle’s ministry had begun on December 14, 1821. By January 1828, his ministry had lost confidence, leading to his resignation and the formation of the Martignac ministry, promoting a policy of moderate liberalism.

The Canuts: June 28, 1828

On June 28, the Society of Mutual Duty by the canuts of Lyon — silk weavers — is founded. It is directed by Joseph Bouvery. This new society emerged from the split of the Society of Mutual Surveillance and Indication founded by Pierre Charnier in 1827. It brings together 8,000 workshop leaders.

War of the Demoiselles: May 25, 1829

In response to a new Forest Code deemed unfair by the peasantry in French localities around the Pyrenees, the so-called War of the Demoiselles breaks out on May 25. It gets its name from the fact that revolting male peasants dressed up as women. The revolt spreads and doesn’t peter out until 1832.

Jules de Polignac Ministry: August 8, 1829

Charles X dismisses the moderate liberal ministry of Martignac, appointing a well-known ultra-royalist Jules de Polignac to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Eventually, Polignac becomes President of the Council of Ministers, leading the government of France from August 8, 1829, to July 29, 1830.

La Fayette Conspiracy: January 19, 1830

The La Fayette Conspiracy, also known as the January Association, also known as the Association of Patriots, was a covert French paramilitary group formed in January 1830, comprising students and workers. Its primary goal was to lay the groundwork for the July Revolution. The movement was meticulously structured, with students recruiting and then overseeing the rebels. The group played a crucial role in orchestrating and initiating the July Revolution, yet its contributions remained largely unrecognized for a significant period. Often, its efforts during the Three Glorious Years are attributed to the broader Schools Movement or seen as part of the collective actions of rebellious students.

Address of the 221: March 2-18, 1830

On March 2, 1830, King Charles X delivered a speech from the throne, threatening the liberal opposition in government and announcing the imminent invasion of Algiers. In response, on March 16, the liberal deputies demand the resignation of opponent ministers. Then on March 18, the Address of the 221 was issued to King Charles X by the Chamber of Deputies at the opening of the French parliament on March 18, 1830. In it, the liberal majority of 221 deputies in the Chamber expressed defiance at the ministry headed by ultra-royalist Polignac. It served as a vote of no confidence against the Polignac ministry and initiated intense political agitation.

Charles X Dissolves the Chamber: May 16, 1830

In response to the Address of 221 on March 16, 1830, expressing the Chamber of Deputies’ mistrust towards the Polignac ministry, Charles X dissolved the Chamber on May 16, hoping to secure a majority aligned with his views through new elections. He scheduled district and departmental elections for June 23 and July 3 respectively. This decision led to a split in the ministry, with resignations and reshuffling of positions, including the introduction of Baron Capelle to head a newly established Ministry of Public Works. Charles urged the public to dispel doubts and maintain order in a proclamation on June 13. However, defying expectations, the Liberals triumphed in the elections held on June 23 and July 19, 1830, securing 274 deputies.

The Algiers Expedition Begins: May 25-June 14, 1830

In the wake of the Fan Affair, French soldiers have been gathering to compose an expeditionary force, which embarks in Toulon on May 25, 1830. A few weeks later, on June 14, the expeditionary force lands in Algiers and begins the French conquest. The expeditionary force of 30,000 to 40,000 men was commanded by General de Bourmont. In part done to serve as a nationalist rallying point around the French monarchy, the French Algiers Expedition fails in this purpose.

Ordinances of Saint-Cloud: July 26, 1830

Published on the authority of Charles X, restricting individual and press freedoms, and dissolving the Chamber. The issuance of these ordinances — which lawyers and political opponents of the regime regard as nonbinding since they’re not laws as well as being unconstitutional — is the trigger for the outbreak of the July Revolution OF 1830. The fact that Charles X’s decreeing of the Ordinances was viewed as illegal and contravening the constitutional settlement of the Bourbon Restoration made the July Revolution widely appealing to the educated class. They, combined with the emergent power of the urban masses, ranging from unskilled wage-earners to master artisans to students, spearheaded the 1830 revolution.

The July Revolution: July 27-29, 1830

Revolution in Paris, the so-called “Trois Glorieuses” (“Three Glorious Days”) takes place. Over the course of these three days, various segments of Parisian society take up arms, build barricades, loot gun stores, attack police stations, destroy royal printing presses, and fight Bourbon government forces. The revolution spreads and, thanks to poor coordination and wanting morale, royalist troops are ineffective at attempts to suppress the disturbances. Charles X and his coterie flee to Saint-Cloud. Last-minute liberal concessions by the Bourbon regime accomplish nothing on July 29, and already the future Orleanist government takes shape.

New Regime, New Dynasty, and Abdication: July 30-August 16, 1830

On July 30, 1830, a manifesto is published that invited the Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe — son of Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, aka Philippe Égalité after 1792, the prince of the blood and relative of Louis XVI who supported the French Revolution — to assume the throne of “King of the French. This initiative is spearheaded by key individuals like long-lived politician Adolphe Thiers, banker Jacques Laffitte, and General Sebastiani, who would all be major personalities of the future Orleanist “July Monarchy.” On July 31, in the night, Charles X and his family depart Saint-Cloud for Trianon, before moving to Rambouillet. There, on August 2, Charles X abdicates and his son, Louis-Antoine d’Artois, countersigns this abdication in favor of the young Duke of Bordeaux. This succession was denied by the emerging Orleanist government, who offered the throne to Louis-Philippe. Between August 3 and August 7, the Charter of the Bourbon Restoration is substantially revised and negotiations with Louis-Philippe hammer out the details of the new regime. On August 9, 1830, the proclamation of the July Monarchy is officially made, with the Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe assuming the position of King of the French, and the new regime is inaugurated. On August 16, Charles X and his family departed Cherbourg for England.

The Bottom Line on the Bourbon Restoration

Inevitability is a dangerous thing in historical analysis, even more so because the benefit of hindsight makes interpreting historical developments as inevitable almost instinctive. We must always be on guard for arguments of inevitability. Was the Bourbon Restoration doomed to inevitable failure? Of course not. But certain contingencies and dynamic developments combined with structural issues of the Restoration regime led to its downfall. The main contingency was the accession of Charles X in 1824. Although he was clearly next in line to the throne, so some might argue his kingship was inevitable, his accession, bringing with it his ultra-royalist, reactionary, pro-Old Regime temperament, still falls under the category of contingency. Had Louis XVIII lived longer, and Charles X had predeceased the former, it is unlikely the July Revolution of 1830 would’ve taken place. It was Charles X and his unrealistic, absolutist vision of restoration, that made the regime lurch toward demise.

The July Revolution and the more liberal regime it established, however, turned bittersweet to many who made the revolution possible. A substantial proportion of the people, from the lowly to the elite, had taken part in the revolution for the ideals of republicanism — not another monarchy, even if it were “more constitutional” and “more liberal” than the Bourbons. This republican discontent would dog the July Monarchy its entire life, culminating in the eventual and much greater Revolution of 1848.