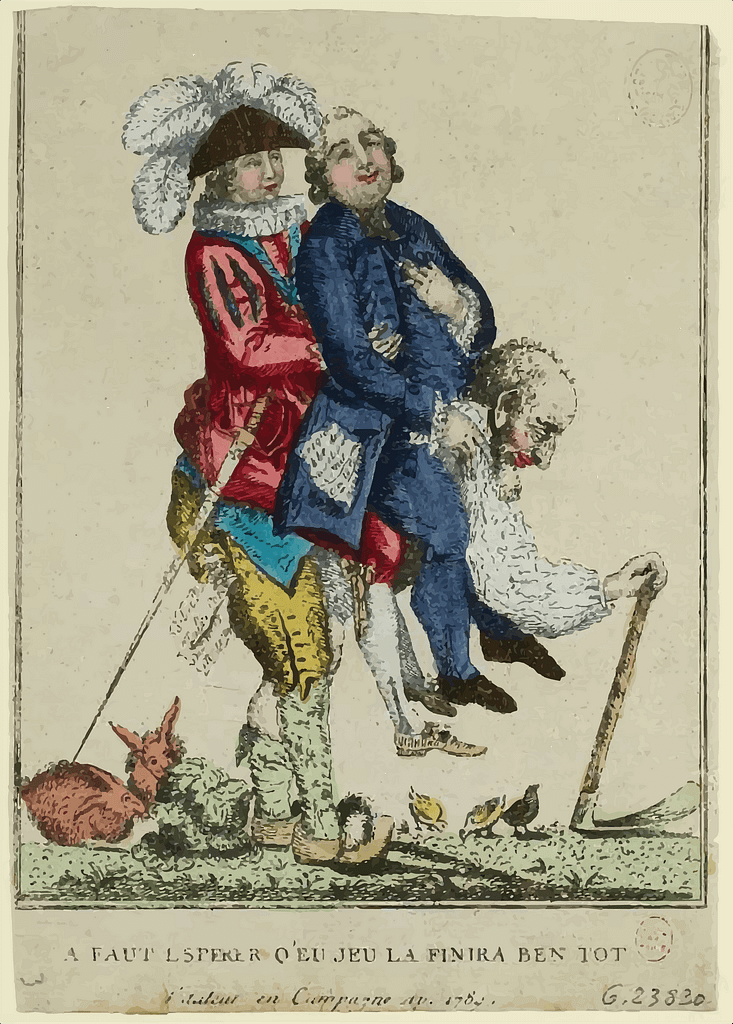

The French Revolution, a period of radical political and societal transformation in France that spanned a decade from 1789 to 1799, indelibly shaped the trajectory of modern history. However, in order to fully understand this seismic event, you have to step backward and read up on pre-revolutionary France, referred to as the Old Regime or Ancien Régime.

Here, we’ve provided a detailed and thorough timeline of French history during the Old Regime. The outline covers 200 years, so settle in for the long road to revolution.

Table of Contents

Timeline of Pre-Revolutionary France

Since the term Ancien Régime can just mean the Old Regime or Former Regime — in contrast to the “new” regime instituted by the 1789 French Revolution — there is no official start date for the beginning of this period in French history. Rather than dip too far back in history, say, to the Middle Ages, we find it makes sense to start with the accession of the Bourbon dynasty in 1589.

The Bourbon monarchs, coming to the throne amidst a furious, brutal, and prolonged civil war — the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) — made concerted efforts to modify the political system. Powerful and rebellious noblemen had plagued the French monarchy during the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) even as the kingdom fought the external enemy, England; during the French Wars of Religion, nobles and noble houses had been at the forefront of politico-religious factions and armies, all of which tore apart the nation for over 30 years. And, while France was officially a Catholic country, the maneuvers made by the Catholic church and clergy during the Wars of Religion — especially in supporting the anti-Bourbon, anti-Huguenot, hardline Catholic League against the monarchy — made the Bourbons suspicious of the power of the church in their kingdom.

August 1, 1589: Assassination of King Henry III of France

Henry III had been trying to steer some kind of middle course between the Huguenots and the Catholic League during his reign. But the forces at play during the Wars of Religion were too great to allow for a “third way” path to emerge. Henry III had become increasingly unpopular and feared being deposed by the noble house of the Dukes of Guise. Henry III made the first move, having Henry I, Duke of Guise (nicknamed “scarface,” Le Balafré) assassinated along with his brother Cardinal de Guise. In reprisal, King Henry III is assassinated by fanatical Dominican friar Jacques Clément. Henry III was the last king of the Valois dynasty.

August 2, 1589: Bourbon Dynasty Succeeds the Valois Dynasty

The Huguenot Henry of Navarre, a distant relative but the heir-presumptive by French Salic law, technically accedes to the French throne as Henry IV — the first king of the House of Bourbon. However, his opponents like the Catholic League and the Duke of Guise do not recognize him.

February 27, 1594: Coronation of Henry IV as King of France

Takes place at Chartres Cathedral after he abjures Protestantism and converts to Catholicism, not to mention defeated all of his opponents in war. This marks the true start of Bourbon monarchy (although he technically became king in 1589, his Catholic opponents in the French Wars of Religion didn’t recognize him) — the dynasty would last until 1789.

April 1598: The Edict of Nantes

Pronounced by Henry IV, putting an end to the Wars of Religion and granting French Protestants religious, political, and civil rights in certain areas of the kingdom. It is an edict of limited toleration and does not recognize Protestantism in France as an official, legitimate religion. Still, it is a seminal step forward that would, unfortunately, be taken back almost 100 years later with the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685.

May 14, 1610: Assassination of Henry IV

By François Ravaillac, a Catholic zealot who stabbed him on the Rue de la Ferronnerie. His son succeeds to the throne as Louis XIII. The reign of King Louis XIII sees an increasing push toward absolutism, especially during Cardinal Richelieu’s tenure in office until 1642.

May 16-October 17, 1610: Regency and Coronation

Since Louis XIII is a minor, a regency is proclaimed on May 16, with Marie de Medici, the wife of Henry IV, as regent. On October 17, the coronation of Louis XIII takes place at Reims Cathedral.

October 27, 1614-February 23, 1615: Last Meeting of the Estates-General

The Estates-General is the national meeting of the three estates of the realm — the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. It would be the last meeting until it was called to meet for the first time in almost 200 years in 1789.

December 2, 1626-February 24, 1627: Last Meeting of the Assembly of Notables

The Assembly of Notables was a consultative body, with members handpicked by the monarch. Still, the Bourbon monarchs of France wanted to shed as much governmental paraphernalia that could be seen as a break on royal power as possible. It wouldn’t be convened again for roughly 160 years — in 1787.

December 25, 1620-June 28, 1629: Huguenot Revolts

Huguenots meet in La Rochelle on December 25, 1620. During this Huguenot general assembly, the decision was taken to resist the royal threats to them by force, and for Huguenots to establish a “state within a state”. This marks the beginning of a series of Huguenot rebellions, lasting from 1620 to 1629. In June 1629, the peace of Alès is promulgated by the king of France Louis XIII after the siege of Ales. The signing of the edict comes after the surrender of La Rochelle, the last Protestant safe haven in France, after a siege of more than a year which ended in 1628, as well as after the sieges of Privas in May 1629 and Alès the following month, which put an end to the attempts at rebellion in the lower Vivarais. The Huguenot rebellions are brought to an end.

May 14, 1643: Death of Louis XIII

Followed by the succession of the very young Louis XIV, the eventual “Sun King” and embodiment of absolutism. The 4-year-old Louis XIV is officially king, but his mother — Anne of Austria — serves as regent during his minority.

May 13, 1648: Start of the Fronde

Beginning in January 1648, the regent and Cardinal Mazarin have been trying to push through the enactment of 7 financial edicts, which customarily must be registered by the Parlement of Paris (the parlements being high courts of appeal as opposed to legislative bodies like the English parliament) in order to be legal and legitimate. These edicts include a tax to be levied on judicial officers of the Parlement of Paris. Not only did the Parlement refuse but on May 13, 1648, the four sovereign courts of France — the Parlement, Chamber of Accounts, Court of Aids, and Grand Council — all unite to condemn the edicts, as well as previous ones, and demand the royal government accede to constitutional reforms crafted by a committee of the four courts. This is the beginning of the Fronde — the greatest challenge to the power of the Bourbon monarchy and political system until 1789, when the French Revolution threw down a new challenge.

October 21, 1652-July 20, 1653: Defeat of the Fronde

The Fronde is brought to an end by a victorious royal government. Louis XIV triumphantly enters Paris on October 21, 1652, moving into the Louvre (a palace at the time, not a museum like today). The signing of peace at Pézenas on July 20, 1653, by the rebellious Prince of Conti. This treaty definitively ends the Fronde of the princes.

March 9, 1661: Death of Cardinal Mazarin

This marks the beginning of Louis XIV’s personal rule and control over the reins of government. He no longer will employ a chief minister like Richelieu or Mazarin for the rest of his reign.

May 24, 1667-May 2, 1668: War of Devolution

The first of Louis XIV’s many wars he would wage as king, with the goal of aggrandizing France and — since he identified himself personally with the state (“I am the state!”) — aggrandizing his own honor and prestige. The war is fought mainly between France and Spain in the Spanish Netherlands (modern-day Belgium), Franche-Comte (an old province that’s now part of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté administrative region), and northern Catalonia in Spain.

April 6, 1672-September 17, 1678: The Franco-Dutch War

This war was waged initially between France and the Dutch Republic before other European power eventually joined in the conflict, sometimes fighting for one side for a bit before jumping to the other. Although Louis XIV’s grand strategic objectives of destroying the Dutch Republic and conquering the Spanish Netherlands were not attained, he still managed to have most of his conquests confirmed in the Peace of Nijmegen.

May 6, 1682: Versailles

Louis XIV officially establishes the French royal court at the Palace of Versailles, moving it from where it traditionally was in Paris.

October 26, 1683-August 15, 1684: The War of the Reunions

Fought between France on one side and Spain and the Holy Roman Empire on the other. Louis XIV continued his push for greater territorial acquisitions and achieved much, but this war would serve as his highwater mark militarily. All of Louis XIV’s wars of aggression, taken together, had now seriously alienated the other European powers and generated the formation of coalitions opposing Louis XIV’s France.

October 25, 1685: The Edict of Fontainebleau

This edict is published, which revoked the limited tolerance and rights granted to French Protestants. The edict has immense implications for the course of French history, as large numbers of French Protestants emigrated leading to a sort of “brain drain”, to the detriment of France and the benefit of her enemies. It also planted the seed of a renewed drive toward achieving tolerance of Protestantism through both popular and political channels — not merely through the whims of one king. Louis XIV employs the use of “dragonnades” to force conversions.

September 27, 1688-September 1697: The Nine Years’ War

Also called the War of the Grand Alliance, it saw Louis XIV’s armies cross the Rhine River and invade the territories of the Holy Roman Empire. This aggressive act, along with the French army’s brutal tactics, stimulated the formation of the Grand Alliance (also called the League of Augsburg) to oppose him militarily. This war marked, if not a decline, the plateauing of France’s power under Louis XIV.

December 20, 1689: Formation of the Grand Alliance

Formed in the Hague, in the Dutch Republic, with the coalition parties including the Austrian Habsburg Empire, the Dutch Republic, England, Spain after 1690, and Savoy from 1690 to 1696. These powers would face down Louis XIV’s France in the Nine Years’ War and again in the War of the Spanish Succession, though with Spain no longer being a member of that Second Grand Alliance.

July 9, 1701-February 6, 1715: The War of the Spanish Succession

An actual global war, it is waged primarily between France and Bourbon Spain on one side and Britain, the Dutch Republic, the Holy Roman Empire, and pro-Habsburg Spain on the other. It is a long, devastating, and exhausting war that ends with the French Bourbon grandson of Louis XIV — Philip of Anjou — being allowed to succeed to the throne of Spain as Philip V, though with any governmental ties or plans of a union of French and Spanish empires completely out of the question. In return, the Grand Alliance powers detached the Spanish Netherlands and much of Spain’s territorial possessions in Italy, giving them to Habsburg Austria, while Britain gained Gibraltar and Menorca. The settlement ending the war established a balance of power that would prevail among the European Great Powers up until the outbreak of the French Revolution and the revolutionary wars in 1789-1792.

September 1, 1715: Death of King Louis XIV

The “Sun King” finally dies after notching up the longest reign in French history. His great-grandson Louis XV becomes king at the age of five. A regency is established and administered by the Duke of Orleans, acting as regent. Part of the deal for the Duke of Orleans to override Louis XIV’s last will and testament — which gave serious powers to his illegitimate offspring, namely, the Dule of Maine — was for Orleans to reach out to the French parlement — the kingdom’s highest appeals court, which had been utterly muffled by Louis XIV during his reign — and gain the parlement’s backing. In doing so, the Duke of Orleans reintroduced the previously hibernating institution and power of the parlements of France.

May 2, 1716: John Law’s System

Creation of the General Bank and the Compagnie d’Occident on May 2, 1716, marked the beginning of Law’s system, named after the Scotsman John Law. The system was quite advanced for Old Regime France, but its collapse in June 1720 would later undermine any idea of creating a central French bank like the Bank of England.

June 24, 1719-December 14, 1720: Mississippi Bubble and John Law’s Fall

He’s made superintendent of the currencies on June 24, 1719. That same year, Law became the architect of what would later be called the Mississippi Bubble, an event that would begin with the consolidation of the various trading companies of Louisiana into a single monopoly — the Mississippi Company — with thousands upon thousands of company shares issued. On January 5, 1720, Law was made Comptroller-General of Finances. Unfortunately, this scheme leads to rampant speculation, followed by panic, as people flooded the market with future shares trading as high as 15,000 livres per share, while the shares themselves remained at 10,000 livres each. By May 1720, prices fell to 4,000 livres per share, a 73% decrease in one year. The rush to convert paper money to coins led to sporadic bank runs and riots. Squatters now occupied the square of Palace Louis-le-Grand and openly attacked the financiers that inhabited the area. It was under these circumstances and the cover of night that John Law fled from Paris, on December 14, 1720, leaving all of his substantial property assets in France. His fall coincides with the collapse of the General Bank (Banque Générale) and subsequent devaluing of the Mississippi Company’s shares.

October 25, 1722-February 23, 1723: Coronation of Louis XV

Takes place at Reims Cathedral takes place on October 25, 1722. But it wouldn’t be until February 23, 1723, that Louis XV is declared of age to rule. This officially marks the end of the regency, however, the Duc of Orléans remained in office as Prime Minister until his death in December 1723.

June 21-August 19, 1726: Cardinal Fleury

Fall of the prime minister, the Duke of Bourbon, and his replacement on June 25 by Cardinal de Fleury (1653-1743). Under Fleury’s auspices, the General Farm (or General Tax Farm; Ferme générale ) is restored on August 19, after the institution foundered due to Louis XIV’s financial difficulties between 1703 and 1726.

June 1730-August 1732: Bull Unigenitus

Declaration of this papal bull as a law of the Kingdom of France. This bull issued by Pope Clement XI condemns Jansenism, and it proves to be very controversial and divisive. Jansenist opposition to it and the movement in general help contribute the growth of the public sphere and public opinion through numerous press publications, helping create the conditions for the revolutionary press and public sphere in the lead-up and during the French Revolution. In August 1732, there’s a crisis in the parlements. Prime minister Cardinal Fleury compels parliaments to register the Bull Unigenitus. Louis XV declared: “The power to make laws and to interpret them is essentially and solely reserved to the king. Parlement is only responsible for overseeing their execution.”

July 8-October 20, 1740: War of Austrian Succession Begins

A conflict originating between Britain and Spain, called the War of Jenkins’ Ear, expands into a larger conflict when Fleury informs the British ambassador that Louis XV has decided to intervene on behalf of Spain, on July 8, 1740. In August, Cardinal Fleury sends two squadrons to America to help Spain in conflict with Great Britain. But then this conflict expands even further into a wider European war when, on October 20, 1740, the Austrian Habsburg Emperor Charles VI dies without male heirs, triggering the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748).

January 29, 1743: Death of Cardinal Fleury

Beginning of Louis XV’s rule without a prime minister. He makes moves to break up the patronage empire that Fleury had put together and nobody was allowed to occupy the same kind of position Fleury held in terms of patronage and access to the king. Under Louis XV, advisory consultations and policy matters were kept largely out of sight, while foreign policy matters were managed via the so-called Secret du Roi — secret diplomatic channels used by Louis XV throughout his reign.

April 24-October 18, 1748: War of Austrian Succession Ends

France, by early 1748, had conquered most of the Austrian Netherlands, but a British naval blockade was crushing their trade, and the state was close to bankruptcy. This stalemate finally resulted in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, with a diplomatic congress assembling on April 24, 1748, and the actual signing of the treaty occurring on October 18. Although the treaty confirmed Maria Theresa in her titles, it failed to address underlying tensions between the signatories, several of whom were unhappy with the terms. France obtained minimal gains despite performing well on the battlefield and expending vast amounts of money, while the Spanish failed to recover Menorca or Gibraltar, which had been ceded to Britain in 1713. The result of this unsatisfactory treaty was the realignment known as the Diplomatic Revolution, in which Austria and France ended the age-old French–Habsburg rivalry that had dominated European affairs for centuries, while Prussia allied with Great Britain. These changes set the stage for the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in 1756.

February 17-27, 1750: The Duke of Richelieu Suspends the Estates of Languedoc

This body was a representative provincial assembly, the regional version of the national Estates-General last convoked in 1614. By order of the king on February 17, the body is suspended. On February 27, the assembly was suspended indefinitely by decision of the Council of State. This marks another step by the absolutist royal government to eliminate alternative, traditional sources of legislative authority in the Kingdom of France.

July 1, 1751: The Encyclopédie

Publication of the first volume of the Encyclopédie, a major literary and intellectual work of the Enlightenment. Its editing and publication is mainly overseen by Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert.

May 17, 1756: Seven Years’ War Begins

Fought from 1756 to 1763, although fighting had been going on in French and British North America since 1754. This massive, exhausting, and global war would end with the complete defeat of France and the loss of several colonies, most notably its continental possessions in North America, although the Caribbean colonies the French retained were far more profitable than their territories in Canada and the Ohio Valley. Still, it was the damage to national honor and the huge debts accrued from the war that severely undermined the French state.

January 5, 1757: Assassination Attempt on Louis XV

Would-be assassin and servant Robert François Damiens attacks King Louis XV with a harmless stroke of the penknife to warn him to think better about his duties. He is drawn and quartered in the Place de Grève on March 28. The rumor, stirred up by the Jansenists, falsely denounced it as a Jesuit plot. In the wake of the attack, the depressed king backtracked. Stunned for a moment by the Damiens attack, provincial parlementaires once again affected from May to September 1757 a protest attitude vis-à-vis royal taxation, in solidarity with their Parisian colleagues.

November-December 1758: Physiocracy

François Quesnay publishes his Tableau Economique at Versailles. The book presents an economic model that laid the foundation of the Physiocratic school of economics. Quesnay believed that trade and industry were not sources of wealth, and instead argued that agricultural surpluses, by flowing through the economy in the form of rent, wages, and purchases were the real economic movers. Though his economic model wasn’t necessarily capitalist, it did signify a break with the more mercantilist economic models of the time.

January 20-25, 1759: Conflict Between Parlement and Intendant

Lettres de cachet order the exile of 22 parlementaires from Besancon, who were in conflict with the royal intendant and first president of the Parlement of Besancon, Bourgeois de Boynes. On January 21 and 22, they are dispersed to different fortresses. Eight other councilors are exiled in turn on January 25, and the exile wouldn’t end until April 1761.

September 20-November 23, 1759: Conflict Between Parlement and the King

A lit de justice is held by the Louis XV at Versailles for the registration of the September financial edicts. The Comptroller General of Finance — Etienne de Silhouette — attempts a tax reform, known as the general subsidy, a set of measures which leads to the taxation of income from all social categories. Louis de Bourbon-Condé, Count of Clermont, holds a lit de justice at the Court of Aids to enforce the registration of three fiscal edicts. The court issued severe remonstrances, calling for a coherent financial policy and denouncing the continual propagation of new, arbitrary regulations. The court wants “a fixed and certain law in the taxation of land and other buildings, a proportional and non-arbitrary law in the taxation of the person, a uniform law in the taxation of consumption”. The general subsidy project fails in the face of the hostility of the privileged estates/orders as well as the aggravation of the mass of taxpayers. On November 13, the Court of Aids sends the king a new remonstrance on the extension of the twentieth provided for in the general subsidy. An early bankruptcy brings Silhouette down on November 23. Bertin, who replaces him as Comptroller-General, abandons the general subsidy but proposed the same types of taxation, direct or indirect, in particular the additional twentieth and the sol per livre of the General Farm.

July 4, 1760: Call for the Estates to Meet Again

The Parlement of Rouen issues a remonstrance, which calls for the restoration of the Estates of Normandy and proposes the motto, “A King, a law, a Parlement.” It’s one of the earlier calls for the re-establishment of the old provincial estate bodies, which had been gradually eliminated as absolutism took firmer hold in France since 1589.

November 13, 1761: Calas Trial

Opening of the trial against the Calas family, brought by the Capitouls of Toulouse — a classic case of superstition and religious authority expanding outside its proper remit. Voltaire defends Jean Calas, a Huguenot condemned without evidence for having killed his son whom he suspected of wanting to convert to Catholicism; in reality, his son committed suicide. Voltaire’s campaign against the Parlement of Toulouse for prosecuting and condemning Calas epitomizes several of the ideals of the Enlightenment.

February 10, 1763: Seven Years’ War Ends

Signing of the Treaty of Paris, ending France’s participation in the Seven Years’ War and included major French colonial cessions to Great Britain, such as the transfer of Canada, part of Louisiana, the Ohio Valley, Dominica, Tobago, Grenada, Senegal, and its Indian Empire to Great Britain. It marks the end of the first French colonial phase, though it did retain some highly profitable Caribbean colonies like Martinique, Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti). Another crucial outcome of the lost war is that France accrued massive debts, which it would struggle to repay for years, especially when French involvement in the American Revolutionary War added another huge load of state debt.

June 5, 1764: Start of the Brittany Affair

This affair featured a showdown pitting the Breton Parlement and the Estates of Brittany against the authority of the French monarchy over an issue of taxation. Two of the main protagonists were La Chalotais (procureur général) at the Parlement of Brittany versus the royal governor of the province, the duc d’Aiguillon. The affair has been seen as a precursor of the French Revolution.

November 26, 1764: Expulsion of the Jesuits

In the aftermath of the La Valette affair (1761), the parlements, expressing their Jansenist, Gallican, and regalist sympathies, succeed in imposing on Louis XV the expulsion of the Society of Jesus — the Jesuits. This resulted in 106 Jesuit colleges being converted to other uses and France’s expulsion was part of a wider European trend of expelling the Jesuits, often justified by the argument that they had accrued so much power that they constituted “a state within a state.”

March 3, 1766: The “Scourging Session”

Also called the “Sitting of the Flagellation” occurs, in which, in a lit de justice, King Louis XV bluntly tells the Parlement of Paris that they have no authority over legislation and all power flows solely from Louis XV’s absolute rule. This session came in response to continued resistance of members of the parlements over the Brittany Affair.

September 16, 1768: René Nicolas de Maupeou

He becomes Keeper of the Seals of France, a key role that assists the Chancellor of France in ensuring that royal decrees were enrolled and registered by the judicial parlements. Maupeou’s position would eventually lead to a major conflict between the parlements and central royal government in the early 1770s.

May 8-August 15, 1769: Conquest of Corsica

French forces defeat Corsican politician and freedom fighter Pascal Paoli on May 8, leading to the complete conquest of Corsica by France. Months later, on August 15, Napoleon Bonaparte was born on the island of Corsica.

April 19, 1770: Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette

The future Louis XVI marries Marie-Antoinette of Austria by proxy in Vienna.

January 21, 1771: Maupeou’s Coup

Also referred to as “the Maupeou Revolution” or “royal revolution”, the parlementaires of the Parlement of Paris are exiled to Troyes. The parlements, which had opposed the royal edicts, were restructured and deprived of their political prerogatives. Confronting their resistance to the financial reforms of Abbé Terray, Maupeou condemns the obstinance and unity of the body of the parlements. Then, faced with their refusal to submit to the royal authority, Maupeou orders the resumption of parlementary activities by force, dispatching musketeers to the residences of the magistrates to banish them and confiscate the charges of parlementaires who refused.

May 10, 1774: Death of King Louis XV

Louis XV dies of smallpox and his grandson, Louis XVI, succeeds to the throne. The new king goes about reforming various parts of the ministry.

August 24-26, 1774: “Saint-Barthélemy of Ministers”

The name “Saint-Barthélemy” is a reference to the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572. This event leads to the disgrace and downfall of Maupeou, who’s forced into exile on his lands, while Miromesnil becomes the new Keeper of the Seals. The comptroller-general Terray was fired, and Turgot moved from the Navy ministry to become the new Comptroller-General of Finances. When he leaves office, Terray leaves a healthy financial situation. The budget deficit was reduced, from 100 million livres in 1769, to 30 million in 1774, and to 22 million in 1776. On August 26, Turgot added Minister of State to his portfolio of positions.

September 13, 1774: Turgot’s Policies

Turgot restores the liberalization of the grain trade, a policy previously carried out by Louis XV’s prime minister Étienne-François de Choiseul (in office from 1758 to 1770) between the years 1763 and 1770. The significance of the liberalization of the grain trade in Old Regime France is that it marked a major change in economic and government policy from the past: Since grain (and, thus, bread) was the staple diet of the peasantry and the urban population, the French royal government saw food security as an essential duty and therefore heavily controlled the grain trade to ensure the national and local balance between demand and supply; however, with the growth of more liberal economic ideas during the Enlightenment (e.g., Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations) a group called the Physiocrats pushed for a “free market” approach to the grain trade as being the most optimal policy in economic terms. On paper, this capitalist approach to the grain trade made sense, but in practice it unfortunately gave rise to speculators who aimed above all for the greatest profit, which led to hoarding of grain to increase its price and/or buying grain from regions where it was cheap and selling in other regions where it was expensive. These results led to the repeal of the first liberalization of the grain trade by Choiseul in 1770. Turgot’s restoration of the “free market” approach would soon blow up in his face.

November 12, 1774: End of Maupeou’s Coup

The new King Louis XVI brings an end to Maupeou’s coup and restores the old parlements. But instead of showing any appreciation for their restoration, the members of the parlements are even more wary of French royal power. Crucially, it was during the Maupeou coup of 1771-1774 that the first calls for convening the national Estates-General take place.

April 18-May 6, 1775: The Flour War

In French, the Guerre des farines, takes place when, after a poor harvests in 1773 and 1774 combined with Turgot’s freeing-up of the grain trade, leads to bread shortages, skyrocketing prices, and hoarding by speculators. Riots and revolts by peasants and city-dwellers erupted in the northern, eastern and western parts of the kingdom of France. Many common Frenchmen see the “free market” approach to the grain trade as disrupting the “moral economy”, meaning that it undermined the principle of the royal government ensuring food security for all its subjects. The “Flour War” once again discredits the liberalization of the grain trade in the eyes of both the royal government and the common people, leading Turgot to reestablish price controls on grain and repeal the act in 1776.

April 19, 1775: American Revolutionary War Begins

The Battles of Lexington and Concord between Massachusetts colonial militia and British regulars marks the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. Three years later, France would officially ally with the American insurgents and directly intervene on their behalf in the war.

January 5-March 12, 1776: Turgot’s Free Market vs Tradition

Turgot proposes to the royal council, on January 5, the abolition of the corporations — corporations in Old Regime France refers to guilds and professional associations like those for lawyers or doctors, which were compulsory and highly regulated, and therefore stifled capitalist, entrepreneurial spirits from being able to whatever they want business-wise — and the royal corvée (essentially a forced labor tax the peasantry had to carry out). Again, while Turgot’s intentions were well-meaning, these liberal economic policies provoked strong resistance from the guilds and other corporative societies because it means the loss of many of their traditional privileges. This resistance induced Louis XVI to hold a lit de justice on March 12 to force the registration of Turgot’s edicts.

May 12-13, 1776: Turgot’s Fall

Facing serious hostility from both political circles (such as remonstrances of the Parlement of Paris) and commercial circles, Turgot resigns. He is replaced by Clugny de Nuits who revokes all reforming edicts over the next six months. At the same time, more observant and intelligent Frenchmen begin to see these privileged corporative bodies as selfish and obstructing greater freedom in society.

October 22, 1776: Jacques Necker

The Geneva banker (and seeming financial wizard) Jacques Necker is appointed Director General of the Royal Treasury. As a Protestant, he could not be a member of the King’s Council and thus could not be appointed Comptroller-General of Finances, hence the alternative title. In order to tackle the budgetary difficulties resulting from France’s still unofficial support for the American rebels, Necker resorts to raising loans both domestically and on international money markets, while at the same time but will returning to the policy of “economies” (aka belt-tightening) carried out by Turgot.

December 28, 1776-June 13, 1777: Franco-American Unofficial Aid

The American ambassador Benjamin Franklin is received by Foreign Minister Vergennes, asking for help from France in their fight against the British. On April 26, 1777, the Marquis de Lafayette departs France for the United States. He eventually lands on North Island near Georgetown, South Carolina on June 13, 1777.

June 29, 1777: Rise of Necker

After the resignation of Taboureau des Réaux, Necker is appointed Director-General of Finances (again because of his Protestantism, it’s an alternative title but essentially the same as Comptroller-General). He will launch a series of loans to finance the French war effort in the American Revolution.

December 17, 1777: Franco-American Relations

King Louis XVI recognizes the independence of the United States on December 17, becoming the first head of state in the world to do so.

January 30-February 6, 1778: Franco-American Alliance

Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the United States and France is concluded on January 30, with each country promising to grant the other the most favored nation clause. The treaty sets out the principle of the freedom of the seas and the right of neutral states to trade with nations at war. Then on February 6, a second treaty — the Treaty of Alliance — intended to remain secret, is signed between France and the United States. It’s technically a defensive alliance in case war breaks out between France and Britain. Notably, the treaty stipulates that neither party can make a peace or truce with Great Britain without first obtaining the consent of the other (a promise which the Americans would later break in order to make peace with Britain and bring an end to the war in 1783).

April 12, 1779: Treaty of Aranjuez

Treaty is signed, renewing of the Family Pact between the Bourbon monarchs of Spain and France. In the treaty, France promises Spain the recovery of Gibraltar, Menorca, Mobile, and Pensacola, lost in various wars against Great Britain over the course of the 18th century.

June 16-July 6, 1779: Spain Declares War on Britain

Charles III of Spain declares war on Great Britain on June 16, shortly followed by the beginning of the siege of Gibraltar by France and Spain on June 24. A Franco-Spanish fleet of 66 vessels and 14 frigates meets in Corunna, on June 25, under the orders of Count d’Orvilliers. On July 2, French forces under the command of Comte d’Estaing defeat British forces and capture the island of Grenada. Later, on July 6, in the Naval Battle of Grenada, d’Estaing ‘s fleet defeats a British one commanded by John Byron, enabling French control of the Caribbean Sea and allows the regiments of the French army, commanded by Rochambeau, to land on American territory.

August 8, 1779: Eliminating Feudal Remnants

An edict on August 8, 1779, abolishes the right of mortmain and personal servitude (serfdom) in the king’s royal domains.

February 25, 1780: The Vingtième

The Paris Parliament registers the February edict extending the second vingtième and 4 sols per pound of the first vingtième until 1790. The vingtième (“twentieth”) was an income tax during the Ancien Régime, based on revenue and required 5% of net earnings from land, property, commerce, industry, and official offices. The vingtième was enacted to reduce the royal deficit. Its eventual expiration date would become a pressing issue in the future, when in the lead-up to the French Revolution the government tried to figure out how to avoid a national default on its debts.

May 2-July 11, 1780: Arrival of French Forces in America

Rochambeau and his expeditionary force of 5,000 men leave Brest, on May 2, and cross the Atlantic. On July 11, Chevalier de Ternay’s squadron — carrying Rochambeau’s expeditionary force — arrives at Newport, Rhode Island.

February 19, 1781: Compte rendu au roi

Necker publishes his Compte rendu au roi (A Report to the King), revealing the state of public finances. Since 1777, Necker had launched 29 loans for a total amount of 530 million livres. By distributing this text with the agreement of Louis XVI, Necker aims to disarm his critics at court. However, the disclosure of the list of pensions granted to courtiers caused a scandal. Not only that, the Compte rendu au roi was manipulated by Necker to show a surplus, when in reality, he merely put the expenditures and debts from the American Revolutionary War in the extraordinary account. But the general public doesn’t know that, so when the French royal government finds itself in dire financial straits in the late-1780s, many Frenchmen don’t understand how this crisis came about and call for the return of Necker.

May 19-21, 1781: Necker’s Fall

Necker resigns after Louis XVI refuses his ultimatum to put him on the King’s Council and returns to Geneva. On May 21, Jean-François Joly de Fleury is appointed Comptroller-General of Finances.

May 22, 1781: The Edict of Ségur

An edict proclaimed on May 22, which requires four degrees of nobility from candidates in the army. Thus, it reserves for the nobility (especially the older nobility) direct access to the ranks of officers without prior service or without passage through military schools. Ségur’s edict was meant to provide poor, old noble families with access to a professional military career as opposed to military offices being bought by upstart new nobles. However, the edict also manages to increase tensions between the bourgeoisie and the nobility because the former see it as an attack on them, and just another sign of how unfair and arbitrary both the society of estates and royal absolutism are.

September 28-October 19, 1781: Siege of Yorktown

This pivotal campaign is waged by Franco-American forces, with Lord Cornwallis finally surrendering on October 19 when his position becomes hopeless after the French naval victory in the battle of the Chesapeake prevents British reinforcements from reaching him. This marks the end of major land campaigning on the North American continent, though not the end of the war entirely.

July 2, 1782: Geneva Revolution

Vergennes, who was one of the loudest voices calling for French intervention on behalf of the republican American revolutionaries, sends an army to crush the Geneva Revolution of 1782, which sought to replace the aristocratic republic with a truly democratic republic. On July 2, revolutionary Geneva surrendered. The Geneva Revolution would prove to be important in the lead-up and during the French Revolution, as several Genevan revolutionary exiles would become leaders in France’s revolution in 1789.

September 3, 1783: The Treaty of Paris

The signing of this treaty puts an end to the American War of Independence. Peace between France, Spain, and Britain is also concluded at the Treaty of Versailles. Britain returns Menorca and Florida to Spain but retains Gibraltar. France recovers its trading posts in India and Senegal, and Great Britain cedes some islands to it in the West Indies. Though France partially got its revenge on Britain for the disastrous Seven Years’ War, the debts and deficits run up by its involvement in the American war would come back to haunt the royal government in 1786.

April 27, 1784: The Marriage of Figaro

The first public performance of this now famous play by Beaumarchais. Its significance derives from the fact that the play questions social inequalities: One of the last lines in the play is, “Nobility, fortune, rank, places, all of this makes you so proud! What have you done for so many goods? you took the trouble to be born, and nothing more.” The eventual revolutionary Danton stated that “Figaro has killed the nobility!”, while Napoleon is supposed to have called it “the Revolution already put into action.”

November 3, 1783: Charles Alexandre de Calonne

Calonne is appointed to the position of Comptroller-General of Finances. He is determined to figure out how to address the glaring problem of France’s national debt. Indeed, interest on accumulated debts absorbs more than 50% of the budget. State revenue reached 475 million livres, against 587 million in expenditure, equaling a deficit of 112 million livres.

August 10, 1784-May 31, 1786: Affair of the Diamond Necklace

Cardinal de Rohan, in a misguided attempt to win the favor of Queen Marie-Antoinette who doesn’t like him, meets Madame de la Motte, who becomes his mistress and later involves him in a plot to act as an intermediary to purchase a fabulous diamond necklace. In January 1785, the Cardinal de Rohan negotiates the purchase of the necklace, but Jeanne de la Motte actually made up this entire scheme of pleasing the Queen and, with her fellow conspirators, take the necklace and sell the diamonds on the black market. On August 15, 1785, Cardinal de Rohan is arrested within the Versailles palace as he was preparing to say mass, interrogated personally by the king, placed under arrest, and marched off in his full cardinal’s attire through crowds of courtiers to the Bastille prison. The reason for this: The discovery of a sordid yet trivial scandal involving a diamond necklace, the Cardinal de Rohan, and a confidence woman that exploded into a public relations fiasco — The Affair of the Diamond Necklace. On May 31, 1786, after a bread-and-circuses of a trial, the court acquits Cardinal de Rohan of any wrongdoing in the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, instead focusing their punishment on the confidence woman, Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, alias Jeanne de la Motte, who set up the whole scheme. Public opinion is very much on the side of the Cardinal. Unfortunately, Marie-Antoinette took the acquittal very personally and ensured, through her husband, that the Cardinal de Rohan was exiled to the Abbey of la Chaise-Dieu.

August 20, 1786: Calonne’s Financial Proposal

Calonne presents to Louis XVI his Précis sur l’administration des finances, which proposes an audacious program of administrative and fiscal reforms inspired by that of Turgot. It includes the creation of the territorial subvention, land tax payable by the nobility and the clergy, conversion of the corvée (essentially a forced labor tax) into a tax in cash, abolition of internal customs, freedom of trade in grain, creation of provincial and municipal assemblies elected by suffrage censitaire without distinction of order.

November 29, 1786-May 25, 1787: The Assembly of Notables Returns

On November 29, 1786, King Louis XVI convenes the Assembly of Notables to meet in 1787, primarily to present Calonne’s financial reform program. From February 22 to May 25, 1787, the Assembly of Notables comes together — the first meeting of the Assembly of Notables since 1626. Calonne’s plan to get his reform scheme the go-ahead from the Assembly of Notables fails, due to a combo of distrust of Calonne and the fact that the Assembly of Notables doesn’t represent France, and therefore cannot legislate any fiscal reforms and taxation — only the Estates-General, the Assembly says, can do that.

February 19, 1788: Society of Friends of the Blacks

Creation of the Society of Friends of the Blacks by journalist and revolutionary Brissot, which advocates for the abolition of slavery in French colonies.

May 3-6, 1788: Resistance of Parlement of Paris

Feeling threatened with suppression by the royal government, they take the lead and by a decree, spearheaded by Jean-Jacques Duval d’Eprémesnil, which spells out what the Parlement saw as the fundamental laws of the realm, emphasizing “the right of the Nation freely to grant subsidies through the organ of the Estates-General regularly convoked and composed,” plus the right of the parlements to register new laws, and the freedom of all Frenchmen from enduring arbitrary arrest (e.g., lettres de cachet); the message also emphasizes the importance of intermediate bodies linked to the society of orders (or estates) as the essential character of the monarchical constitution. This view of the fundamental laws of the realm is in opposition to the ideals of absolutism. On May 5 and 6, the Marquis d’Agoult, captain of the guards, attempts to arrest the councilors Epremesnil and Montsabert in the middle of a session. Protected by their colleagues, they manage to escape but ultimately give themselves up the next day.

June 7, 1788: The Day of the Tiles

In French, Journée des Tuiles, in Grenoble occurs. It’s arguably the first open revolt against the king and royal policies pushed through by Étienne Charles de Brienne, minister of finance from 1787 to 1788.

July 21, 1788: The Assembly of Vizille

This assembly convenes what in actuality is essentially the Estates-General of Dauphiné, a province. Claude Perier, inspired by all of the liberal ideas around him, assembled a meeting in the room of the Jeu de Paume (indoor tennis court) in his Chateau de Vizille and hosted this meeting, which was previously prohibited in Grenoble. Almost 500 men gathered that day at the banquet hosted by Claude. In attendance there were many “notables” including churchmen, businessmen, doctors, notaries, municipal officials, lawyers, and landed nobility of the province of Dauphiné. The demands sounded out at this meeting aligned with the sentiments of many Frenchmen: The convocation in Paris of the national Estates-General, echoing some prominent voices in the Assembly of Notables (like Lafayette) as well as the calls for the Estates-General dating back to the exiled members of the parlements during Maupeou’s coup (1771-1774), when he tried to completely restructure the court system and neutralize the power of the judiciary. What’s important about the Assembly of Vizille is that it marks a step toward far more open opposition to the absolutist monarchy. with increasing support for its demands from diverse corners of society. Two lawyers who led much of this meeting would go on to play critical roles in the early phases of the Revolution: The Protestant Antoine Barnave and Jean-Joseph Mounier.

August 8-25, 1788: France Is Bankrupt

The royal treasury is declared empty, and the Parlement of Paris refuses to reform the tax system or loan the Crown more money. To win their support for fiscal reforms, the Minister of Finance, Brienne, sets May 5, 1789, for a meeting of the Estates-General, the national assembly of the three estates (or orders) of the realm: The First Estate, the Clergy; the Second Estate, the Nobility; and the Third Estate, commoners (ranging from peasants to wealthy bourgeoisie; basically defined as those that don’t belong to either the First or Second Estate). On August 16, 1788, the treasury suspends payments on the debts of the government. As a result, the Paris Bourse (stock exchange) crashes. Then, on August 25, Brienne resigns as Minister of Finance, and is replaced by the Swiss banker Jacques Necker, who is popular with the Third Estate, in part because he seemingly financed France’s involvement in the American Revolutionary War while at the same time producing a surplus on the balance sheet. French bankers and businessmen, who have always held Necker in high regard, agree to loan the state 75 million, on the condition that the Estates-General will have full powers to reform the system.

December 27-29, 1788: Third Estate Is Doubled

Over the opposition of the nobles, Necker announces that the representation of the Third Estate will be doubled, and that nobles and clergymen will be eligible to sit with the Third Estate. What’s more, on December 29, Marseilles calls for an increase in the number of elected members of the Third Estate and also for voting by head in the Estates-General.

French Revolution Begins: 1789

Here is where our timeline of Old Regime France comes to an end. The year 1789 marks the beginning of the monumental and world-shaking event that is the French Revolution. In January 1789, French intellectual, writer, and member of the clergy Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès publishes his famous and highly influential political pamphlet, What Is the Third Estate? (Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État?). It electrifies public opinion and helps garner popular support for giving more power to the Third Estate. On February 7, 1789, orders are given for the estates to draw up customary notebooks of grievances (cahier de doléances) in anticipation of the meeting of the Estates-General. Riots occur in Paris in late April, fueled by workers of the Réveillon wallpaper factory in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine who mistook a statement about fixing wages at a livable level as meaning that wage cuts were about to take place. Twenty-five workers were killed in battles with police.

On May 2, 1789, the presentation by order of the 1,200 deputies to King Louis XVI at Versailles, during the grand opening procession of the Estates-General, which convenes for the first time since 1614 on May 5. The Estates-General was nominally convoked by finance minister Jacques Necker to help solve the kingdom’s dire financial straits. However, very soon, the representatives elected to the Estates-General move beyond this narrow remit and discuss the implementation of political, not just fiscal, reforms. Between June 10 and 14, at the suggestion of Sieyès, the Third Estate deputies decide to hold their own meeting and invite the other Estates to join them. Nine deputies from the clergy decide to join the meeting of the Third Estate on June 13-14, 1789. On June 17, the Third Estate votes to leave the Estates-General and form a new body of government, calling itself the National Assembly, led by Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau.

Then, the dominos really begin to fall. On June 20, 1789, the famous Tennis Court Oath takes place (Serment du Jeu de Paume). The Tennis Court Oath came about after the bodies comprising the Estates-General — the clergy, the nobility, and the Third Estate — reached an impasse over issues of representation, especially on the question of voting by order or voting by head, the latter of which would benefit the more numerous Third Estate representatives. The Third Estate representatives moved to meet in the royal tennis court because, on the morning of June 20, when they arrived at the chambers of the Estates-General, the door was locked and guarded by soldiers. Interpreting this as an attempt to try and silence them, or outright suppress them, the Third Estate instead held their own congregation in the nearby tennis court, where they swore “not to separate and to reassemble wherever necessary until the Constitution of the kingdom is established.” Soon, on June 25-27, Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (later known as Philippe Égalité because of his commitment to the Revolution), leads 48 nobles to join the National Assembly. Partly due to this, on June 27, Louis XVI changes course, instructs the nobility and clergy to meet with the other estates, and recognizes the new Assembly. However, at the same time, Louis XVI orders reliable military units, primarily composed of Swiss and German mercenaries, to gather in Paris. On July 9, the National Assembly becomes the National Constituent Assembly.

Finally, that seminal event occurs: On July 14, 1789, a large armed crowd, including both armed civilians and the mutinous French Guards (Régiment des Gardes françaises), besieges and eventually storms the Bastille, a symbol of arbitrary absolute rule of the Bourbons.

The Bottom Line on the Timeline of Old Regime France

The 200 years spanning from the accession of Henry IV in 1589, the first Bourbon king of France, to the storming of the Bastille in 1789, contain all the traits that epitomize Old Regime France: The absolutism and ostentation of Louis XIV, “the Sun King”; the gradual encroachment of royal authority into all areas of society, undermining the traditional role and responsibilities of the landed nobility; centralization of governmental power through the establishment and use of intendants, answerable only to the king; a blossoming of literary and intellectual culture, most encapsulated in the Enlightenment and the “republic of letters”; masque balls intermingled with ceaseless international wars; and constant dire financial straits.

Pre-revolutionary France, like most European states at the time, was a society composed of estates/orders and corporative bodies, like guilds, professional associations, colleges, hospitals, religious orders, and village communes. As in other Early Modern European countries, society was not seen in terms of individuals adding up to a larger whole, with civil and political rights tied to the individual. Instead, civil and political rights came only with the social group you were a part of, be it a peasant member of a village commune or a low-level baron who was a member of the Second Estate. Ultimately, what France faced by 1789 were the internal contradictions produced by a society transforming from a hierarchical, corporative social order, to one based on public opinion and the individual citizen.